Symptoms and diagnosis of perforation

A small hole in the nasal septum may not manifest itself for a long time. But against this background, the risk of infection or breathing problems increases. Therefore, the main symptoms of a hole in the nasal septum are the manifestations of the complications that it causes. These include:

- The appearance of a whistling sound when inhaling and exhaling through the nose;

- Nasal congestion and difficulty breathing;

- Feeling of dryness, discomfort, less often – pain in the nasal cavity;

- Bleeding from the nose or purulent discharge, often with a foul odor;

- If the perforation of the nasal septum is large, there will be a noticeable external change in the shape of the nose (for example, a “saddle nose”, when the back of the nose appears to have sunken in).

Only a doctor can diagnose the presence of a hole in the nasal septum after examining the nasal cavity - rhinoscopy . However, in addition to detecting the hole, the doctor needs to conduct additional examinations and tests (complete blood count, test for syphilis, etc.) to exclude the recurrence of the problem.

In our clinic you can undergo surgery to correct the nasal septum. See detailed prices and costs here.

Perforation of the nasal septum (NSP) is usually considered a rather rare pathology in the practice of an otolaryngologist. However, according to the only known epidemiological study, the prevalence of this disease in the population is 0.9% [1]. Most often (in approximately 60% of cases), perforations occur after surgical interventions on the nasal septum (NS), when ruptures of mucoperichondrial flaps, which are inevitable in many cases, occur or tissue detachment (preparation) is performed in the submucosal layer, and not between the cartilage and perichondrium [2— 5]. Other iatrogenic factors include transnasal intubation, cryosurgery and cauterization of bleeding vessels on opposite surfaces of the PN [6], as well as prolonged nasal tamponade. Other known causes of PPN are nasal trauma, hematoma or abscess of the PPN [7–9], exposure to toxic substances, and use of cocaine, which has a powerful vasoconstrictor and thrombotic effect. All these factors reduce the volume of blood flow in the mucous membrane of the PN and lead to disruption of trophic processes in the thickness of the cartilage [7, 9—11]. Among the drugs that can contribute to the formation of PPN in a number of situations are topical glucocorticosteroids [12, 13]. We should not forget that PPN can sometimes be the only symptom of such systemic diseases as rheumatism, Still's disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Raynaud's disease, Wegener's granulomatosis and other systemic vasculitis, as well as accompany chronic inflammatory diseases of the paranasal sinuses [10, 14]. An independent group consists of so-called “spontaneous” perforations, when the cause of the disease cannot be clearly established.

In the latter case, a violation of the aerodynamic conditions in the nasal cavity, for example, due to curvature of the nasal cavity, causes the development of the phenomena of chronic atrophic rhinitis. Changing the direction of the inhaled air stream causes dryness of the mucous membrane and the formation of crusts in the nasal cavity, which patients try to remove on their own, introducing additional infection into the already injured mucous membrane of the nasal cavity. The associated secondary infection causes inflammation of the mucous membrane, then necrosis of the cartilage and leads to the formation of perforation [12, 15-17].

In the presence of PPN, the stream of inhaled air, breaking up into small streams at the level of the posterior edge of the perforation, acquires a turbulent movement instead of laminar. This further enhances its drying effect, especially in the anterior sections, which leads to increased perforation, scant but regular, often daily bleeding, headache, foreign body sensation and difficulty in nasal breathing. With small perforations, patients note an unpleasant whistling sound when inhaling [7, 18].

PPNs differ in size, shape, location, presence or absence of a framework around the perforation, and the condition of the edges, and therefore cause different symptoms in patients [5, 14, 16, 19]. The type of perforation influences the choice of treatment tactics. Slit-like PPNs in the lower and posterior sections that do not cause complaints—so-called “silent” perforations—usually do not require surgical intervention [20]. Perforations in the anterior parts of the PN, which cause the greatest concern to the patient, usually require plastic closure by surgery [3, 7, 15].

Symptoms of PPN that force the patient to see a doctor are frequent nosebleeds, crusting, dryness, sometimes an unpleasant odor, difficulty in nasal breathing, whistling when breathing, headache, as well as cosmetic defects - retraction of the columella and retraction of the nasal bridge [3, 21] .

When discussing which PPNs cannot be closed surgically, we must keep in mind not only their large size and the lack of a sufficient amount of plastic material (mucous membrane and cartilage), but also those cases where the perforation formed due to systemic diseases or tumor process. The effect of surgical treatment should not be expected [15, 22, 23].

The purpose of this study is a retrospective analysis of the results of operations performed for PPN.

Patients and methods

In the period 2005-2011. in the clinic of ear, nose and throat diseases of the First Moscow State Medical University (formerly MMA) named after. THEM. Sechenov, we examined 86 patients diagnosed with perforation of the nasal septum. Among them, 22 patients were admitted for a biopsy of the mucous membrane from the edge of the PPN and to exclude systemic diseases that could contribute to its formation (13 of them were diagnosed with Wegener's granulomatosis). Six patients in whom PPN formed after a previously performed submucosal resection and did not cause complaints, underwent only surgical interventions for concomitant pathology: radio wave reduction of the inferior turbinates (3), endoscopic polysinusotomy for chronic sinusitis (2) and rhinoplasty - removal of the hump nasal dorsum with rotation of the nasal tip (1). Another four patients with perforation with a diameter of more than 3 cm and complaints of persistent difficulty in nasal breathing underwent submucosal resection of curved sections of the PN located anterior or posterior to the perforation.

The remaining 54 (62.7%) patients in this series underwent plastic closure of the PPN. This group of patients included 26 women and 28 men, ranging in age from 15 to 56 years (mean age 32.1 years). In all examined patients, a thorough analysis of complaints was carried out, anamnesis data were assessed, an endoscopic examination of the nasal cavity was performed with photo and/or video documentation of the identified findings, a smear was taken from the posterior edge of the perforation for microflora and sensitivity to antibiotics, the condition of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses was assessed according to the data. computed tomography. If Wegener's granulomatosis was suspected, a test for antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA) was performed; in case of spontaneous perforations, a biopsy of the mucous membrane and cartilage was performed during surgery from the posterior edge of the perforation.

As preoperative preparation, patients independently washed the nasal cavity with an isotonic solution of sea salt (Aqua ENT, Marimer preparations), instilled or injected peach oil or oil solutions of vitamin A and E into the nose using tampons, and used ointments with dexpanthenol. Some patients with perforation sizes larger than 1 cm and a large number of bloody crusts were prescribed applications of methyluracil ointment. The symptoms of the disease subsided somewhat during conservative treatment before surgery, but not a single patient experienced their complete disappearance or significant improvement in well-being, which prevented them from abandoning surgical treatment.

Indications for plastic closure of PPN in our observations were perforations, gradually increasing in size, with ulcerated edges, which were manifested by periodic bleeding, PPN of small sizes in the anterior section, causing whistling when breathing and also tending to gradually “grow”, cases where the cause the formation of perforation remained unclear.

Forty-seven patients underwent plastic closure of the PPN using endonasal access using only local tissues; in 4 patients, a mucosal flap from the vestibule of the oral cavity was additionally used. In 3 cases, the operation was combined with the elimination of saddle nose deformity and was performed using an open rhinoplasty approach.

Operation technique.

Under combined endotracheal anesthesia with infiltration of the mucous membrane of the PN with a solution of articaine with adrenaline (Ultracaine Forte), a semi-penetrating incision was made in the area of the caudal edge of the quadrangular cartilage on the left, which was continued downward and laterally along the bottom of the nasal cavity, parallel to the edge of the piriform opening to the attachment point of the anterior end of the inferior nasal turbinate .

If the perforation was significant (when the height of the PPN was more than 1.5 cm), towards the dorsum of the nose, the incision was extended to the lower edge of the triangular cartilage, along it, to the level of the limen nasi

. The mucoperichondrium was separated using a blunt and sharp method to the anterior edge of the perforation, then the mucous membrane was prepared subperiosteally from the lower edge of the pyriform opening towards the choana, thus preparing a mucoperiosteal flap from the bottom of the nasal cavity. After a bordering incision along the edges of the PPN, the mucoperichondrium and mucoperiosteum were separated from the preserved sections of the PPN skeleton on both sides, refreshing the perforation edges at the same time. The remains of the cartilaginous skeleton and curved bone sections were resected using scissors and Blakesley forceps. The formed flaps of the mucous membrane were moved from the bottom of the nasal cavity upward, and from the upper parts of the nasal cavity - downward. As a result, the perforation became slit-like, and it was important to ensure that the edges of the PPN on both sides were aligned without tension. The edges of the perforation were sutured (Vicryl 4.0). The movement and suturing of the flaps was supplemented by reimplantation of straightened remnants of quadrangular cartilage into the area of the defect; in 2 cases, when there was a lack of plastic material in the PN itself, auricular cartilage was used (Fig. 1, color insert).

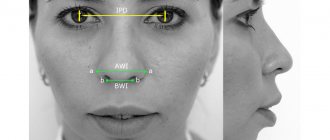

Figure 1. The main stages of plastic closure of perforation of the nasal septum (end endoscope).

a - semi-penetrating incision and separation of the mucoperichondrium to the anterior edge of the PPN; b — separation of the mucoperichondrium and mucoperiosteum behind the posterior edge of the PPN; c — moving the flaps and matching the edges of the PPN; d — resection of the remains of the quadrangular cartilage and bone skeleton; d — suturing of flaps; e — reimplantation of straightened sections of the quadrangular cartilage into the defect area. Designations: 1 - quadrangular cartilage; 2 — perforation with a diameter of 1.0 cm; 3 - flap of the mucous membrane. In case of large sizes of the PPN and the impossibility of matching the edges of the perforation due to a lack of mucous membrane on one or both sides, a racket-shaped flap of the vestibule of the oral cavity was formed with the base at the lower edge of the pyriform opening. Such a flap (or flaps) was passed through the formed canal into the anterior parts of the nasal cavity and sutured to the mucous membrane of the edges of the perforation, thus filling the remaining defect. Finally, sutures were placed along the incision line, taking care not to increase the tension on the flaps.

Silicone stents were installed on the PN and secured with transseptal sutures (Vicryl 2.0). Elastic tampons were placed in the nasal cavity and removed after 24 hours. To prevent infectious complications during surgery, 1.0 antibiotic from the third generation cephalosporin group (ceftriaxone) was administered intravenously; in the postoperative period, antibiotic injections were continued intravenously or intramuscularly for 5-7 days at the same dose.

In the postoperative period, patients also received symptomatic therapy according to indications: analgesics, hemostatic drugs, dexamethasone at a dose of 8-12 mg/day intravenously (for severe swelling of the tissues of the nasal cavity). Starting from the second day after surgery, patients were injected with solcoseryl gel under the stents, nasal toilet was performed 2-3 times a day using a suction tip, and turundas with an ointment containing hydrocortisone, lanolin and olive oil were installed in the nasal cavity. All this time, the patients independently rinsed the nasal cavity with an isotonic sea salt solution. The stents were removed on days 12–14 after surgery. On repeat visits, nasal toilet was performed in a similar way, while the patients continued irrigation therapy and, when crusts formed, they independently injected methyluracil ointment or vegetable oils into the anterior parts of the nasal cavity.

At follow-up examinations after a month and in a longer period, we performed a repeat endoscopic examination of the nasal cavity with photo and/or video documentation.

Results and discussion

After analyzing the anamnestic data, it became clear that in 31 (57.4%) patients, perforation occurred after previous surgical interventions on the PN. Three patients (5.6%) associated the occurrence of perforation with a previous nasal injury. In one patient (1.8%), PPN developed due to long-term use of intranasal corticosteroids. In 19 (35.2%) patients, the cause of PPN formation remained unclear. These perforations were classified as spontaneous. In all patients of the study group, the presence of PPN was clinically manifested. The most common complaints in patients operated on for PPN were persistent crusting (96.2%), difficulty in nasal breathing (46%), nosebleeds (22%), and whistling when breathing (22%). According to endoscopic examination, all perforations were localized in the cartilaginous part of the PN, and their sizes ranged from 0.3 to 2.7 cm. In 52 cases, the PN had a round or oval shape, in two cases it was slit-like. The posterior edge of the perforation was ulcerated in 41 (75.9%) patients. The cartilaginous framework around the edges of the perforation was absent to a greater extent in patients who had previously undergone surgery for PN.

During microbiological examination of nasal cavity smears, growth of Staphylococcus aureus

(105-108 CFU/ml), in 13.3% -

Staphylococcus epidermidis

(101-105 CFU/ml), in 6.7% -

Acinetobacter lwoffii

(106 CFU/ml), in 6.7% -

Escherichia coli

( 106 CFU/ml), in 6.7% -

Neisseria

spp. (104-106 CFU/ml), in 20% of patients - combinations of various microorganisms.

In 31 (62%) patients in this group, the presence of perforation was combined with curvature of the PN, in 10 (18.5%) - with symptoms of vasomotor or hypertrophic rhinitis. Computed tomography was performed in 26 operated patients. According to this study, in 7 (12.9%) patients PPN was combined with pathology of the paranasal sinuses: chronic sinusitis (5.55%), cysts of the maxillary sinuses (3.7%), polypous rhinosinusitis (3.7%) (Fig. 2 on color insert).

Figure 2. Options for combining perforation of the nasal septum with other ENT pathology. CT, axial projection. In 4 (7.4%) patients, in addition, there was a saddle-shaped deformity of the nasal dorsum, in 4 (7.4%) patients, the presence of synechiae of the nasal cavity formed after previous surgical interventions was noted, in 1 (1.85%) during examination, insufficiency was diagnosed nasal valve In this regard, in addition to plastic closure of the PPN, these patients simultaneously underwent submucosal vasotomy of the inferior turbinates or submucosal osteoconchotomy, rhinoplasty, excision of synechiae of the nasal cavity, correction of the nasal valve, as well as endoscopic operations on the paranasal sinuses (see table).

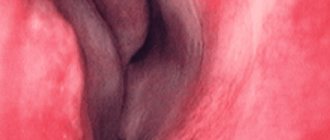

As a result of the operations performed, complete closure of the PPN was noted in 34 (63%) patients (Fig. 3, color inset),

Figure 3. Endoscopic examination of the nasal cavity (end endoscope). in 17 (31%) it decreased, in 3 (6%) there was a slight increase in the size of the perforation. We also considered the reduction in the size of the PPN and its posterior displacement to be a satisfactory result, since in this case re-epithelialization of its edges occurred and the symptoms of the disease that bothered patients before surgery almost completely disappeared. In all cases, in the long-term postoperative observation period, from one month to six months, patients noted an improvement in general well-being, improvement in nasal breathing, disappearance or, in cases where perforation persisted, a decrease in pre-existing complaints.

In cases where perforation occurred after previous interventions on the PN or trauma to the nose, its complete closure was observed in 26 (76.4%) patients out of 34; in 7 (20.6%) the PN decreased in size and moved posteriorly. In 1 (3.0%) observation, due to a viral infection in the postoperative period, the PPN slightly increased in size. In 19 cases of spontaneous perforations, a successful outcome of the operation was observed in 7 (36.8%) of them, when the perforation closed completely, and in 10 (52.7%), when it decreased in size, moving upward and/or posteriorly. In 2 (10.5%) patients there was a slight increase in PPN. It was noted that in cases where the PPN did not close completely, it initially measured about 1.5 cm in height and more than 2.0 cm in length. In one case, spontaneous perforation, despite its small size - 0.3 cm, increased to 0.5 cm. Thus, complete closure of spontaneous PPN is observed in a smaller percentage of cases compared to post-traumatic perforations. This may be due to the fact that this group of patients has a higher contamination of the nasal mucosa with Staphylococcus aureus

, the phenomena of atrophic rhinitis are more pronounced. It is also impossible to exclude the influence of factors unknown to us, in particular those that contributed to the emergence of PPN.

In samples of the mucous membrane taken from the posterior edge of the PPN, signs of chronic inflammation, the phenomenon of sclerosis, acanthosis and tissue necrosis were revealed. In biopsy samples of the quadrangular cartilage, its dystrophic structure was noted.

By retrospectively analyzing the results of insufficiently effective operations, it is possible to identify possible causes of relapses of PPN after an attempt at their plastic closure:

- layering of a viral infection - this reason was clearly visible in 2 (3.7%) patients in whom perforation re-formed in the early postoperative period, despite perfectly performed suturing of the edges of the perforation;

- possible persistence of staphylococcal infection in the nasal cavity;

— application of transseptal sutures in cases where the edges of the perforation could not be adequately sutured with conventional interrupted sutures due to excessive thinning and loose structure of the mucosal flaps;

- large size of stents, too tight tamponade of the nasal cavity, causing additional tension on the edges of the perforation and cutting of the sutures.

conclusions

1. According to our data, in 62.7% of cases the presence of PPN is an indication for surgical treatment. Attempting plastic closure should be avoided in cases where the PPN is not clinically manifest, is located in the posterior regions, and is a consequence of previous surgery on the PPN.

2. According to a microbiological study, in 46.6% of patients with PPN, Staphylococcus aureus

.

3. Complete closure of the PPN was achieved in 63% of operated patients. In cases where it is not possible to achieve complete closure, but the PPN decreases and moves posteriorly, patients also note an improvement in well-being, a decrease or complete disappearance of complaints that existed before the operation. The result of the operation in many cases depends not only on the surgical technique, but also on a number of other reasons that currently remain unknown.

Prevention of perforation of the nasal septum

A hole or hole in the nasal septum can form for the following reasons:

- Injuries to the nose, not removed large hematoma in the septum area;

- Purulent foci localized in the area of the nasal septum;

- Infections that contribute to the destruction of cartilage tissue (including syphilis, tuberculosis);

- Malignant neoplasms in the septum area;

- Dry atrophic rhinitis;

- Diabetes;

- Abuse of vasoconstrictor drops or sprays with corticosteroids;

- Use of certain types of drugs that are usually administered through the nasal passages;

- Systemic diseases affecting connective tissue (for example, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus);

- Complications of surgical operations in the nose area.

Therefore, timely treatment of respiratory tract infections (rhinitis and sinusitis), as well as a reasonable approach to choosing a surgeon if nose surgery is necessary, and the use of drops and other medications only in strict accordance with the doctor’s recommendations are of great importance in the prevention of perforation of the nasal septum.

Effective prevention of this problem is also facilitated by annual preventive examinations with an ENT doctor and early diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases (diabetes, etc.).

When does perforation of the maxillary sinus floor occur?

In ordinary life, perforation is impossible; it always becomes a complication of any dental manipulations with the upper teeth. Perforations occur during root removal, during installation of implants, and during the treatment of pulpitis. At the same time, a gross violation of treatment tactics by the doctor, as well as the special structure of the skull and the anatomy of the teeth can become a source of trouble for a person.

For example, the risk for the patient increases many times if preliminary radiography reveals too small a distance between the apex of the tooth root and the bottom of the maxillary sinus.

There is also danger if the doctor tries too hard to expand the root canals or fills them with excessive compaction. The filling material, transforming, is able to go beyond the apex of the tubule; subsequently, the sinus is perforated in almost one hundred percent of registered cases.

A breakthrough can also occur when installing a pin or inserting an implant. In the latter cases, it is always the dentist's mistake. Such an accident significantly complicates further procedures when performing prosthetics. The jaw bones of patients who have lost their teeth long ago and applied late for implantation are extremely vulnerable. If a tooth is removed, the processes of tissue degeneration accelerate. The doctor must take this feature into account when determining the size of the pin and performing pre-implantation preparation.

Perforation also occurs during root resection if the dentist did not bother to carefully study the patient’s examination data in advance and does not know the size of the bone plate that separates the maxillary sinus and the inflamed cyst on the tooth. Inaccurate movement and perforation occurs. It can also be caused by surgery to remove a significant amount of jaw bone.

Treatment of perforation of the nasal septum

A hole in the nasal septum can only be repaired surgically. How septal plastic surgery will be performed depends on the size of its defect.

If the size of the hole in the nasal septum is up to 5 cm, then plastic surgery of the septum is performed by closing the hole with a flap of the mucous membrane. Very small holes can be removed simply by stitching their edges.

To eliminate larger defects of the nasal septum, artificial implants or transplants of the patient's own tissue are used.

An important task in the treatment of septal perforations is not only to restore its integrity, but also to eliminate the cause of this problem. If it is impossible to completely remove the cause (for example, diabetes, etc.), you should follow all the doctor’s recommendations for the prevention of complications and the recurrence of septal defects.

Diagnosis of pathology

A doctor can confirm the diagnosis after examination.

First of all, the doctor examines the septum to determine damage to soft and hard tissues. This examination technique is called rhinoscopy and is carried out using a special rhinoscope device.

The patient is also prescribed blood and urine tests to determine the presence of an infectious disease. An accurate diagnosis is established based on the results of examination and laboratory tests.

Damage can be of various types. Violation of the integrity of the nasal septum occurs both as a result of the use of drugs and after surgery. If it is impossible to determine the cause of septal perforation, the specialist will prescribe additional studies.

Conservative treatment

If a person does not have obvious signs of perforation and does not feel discomfort, special therapy is not needed.

Antibiotics

This category of medications is used only if there is clear confidence in the development of a bacterial infection. For chronic nasal lesions, antibacterial ointments are indicated. These include Bactracin and Bactroban.

Moisturizing and cleansing

If the hole is small, doctors advise maintaining normal moisture in the mucous membrane. For this purpose special substances are used. It is also worth lubricating your nose with products that contain Vaseline.

If a person experiences serious discomfort due to the appearance of crusts, doctors advise rinsing the nose more often. To do this, you can use special substances containing sea water. Emollient ointments and other medications are also used.

Causes

The key factors that lead to perforation of the nasal septum include the following:

- Surgical interventions performed by unqualified doctors (for example, nose surgery).

- Infections that destroy cartilage.

- Systemic lesions of connective tissues.

- Atrophic rhinitis.

- Traumatic injuries to the nose of various types, lack of treatment for hematomas.

- Tumor formations in the nose.

- Drug use.

One of the factors in the appearance of perforation is the constant influence of toxins on the nasal cavity. This is most often observed when exposed to harmful production factors.

Inspection of the nose for septal perforation:

Preventive actions

The patient is unable to prevent a perforation of the maxillary sinus, and if this happens, he will not be able to overcome what happened without the help of a doctor. But an experienced dentist has the right to take measures to prevent an undesirable scenario. To do this, you will need to conduct a high-quality preliminary examination of the anatomical features of the person applying to the clinic and strictly follow the method of medical manipulation.

Having caused perforation, the doctor is obliged to draw up a treatment plan and bring the patient to a favorable outcome. And a person who experiences disturbing sensations after tooth extraction, treatment of pulpitis, or in other cases, should not endure and remain silent. A timely visit to the clinic will prevent the development of serious complications.

Consequences of perforation

The patient should not expect that the perforation will heal on its own; such a wound should not be perceived superficially. Attempts at self-treatment with folk remedies or opening a fistula at home are prohibited. The consequences of careless intervention look ominous:

- Loss of healthy teeth in close proximity to the perforation site;

- Penetration of infection into other intracranial cavities;

- Development of abscesses and phlegmons with extremely serious health consequences;

- The risk of developing meningitis or meningoencephalitis due to the proximity of the brain to the inflamed lesions inside the maxillary sinus. With each act of sneezing, being under great pressure, the pathological flora scatters inside the cavities and is able to penetrate into areas from where it is easy to affect the meninges. All this can lead to death.

Therapy of old perforations overgrown with fistula tracts is usually complex and time-consuming. Relapses with new breakthroughs from the sinus to the gum surface are common. Fistulas are not at all harmless formations; they are not easy to cure.